Hey Netflix and the rest of the internet, pull up a chair, you have so much to learn from standards-based grading practices.

The Wall Street Journal ran an article “When 4.3 Stars is Average: The Internet’s Grade-Inflation Problem” which highlighted the move Netflix made in April of 2017 to shift from a five-star feedback rating system to a binary thumbs up and thumbs down model. “You get more ratings when you have fewer decision points,” was the logic provided by Netflix’s vice president of productive innovation, Todd Yellin.

The idea of having fewer levels of measurement to more objectively and accurately measure performance is a critical component of an SBG model. In fact, this is a rallying cry of SBG advocates who rightly argue that moving from a 100 point percentage system to a 3 or 4 level standards-based system, for example, can do far more to provide specific and meaningful feedback.

However, over a year later, Netflix is still struggling to get it right and critics are voicing their concerns. These thumb ratings feed into a “Percent Match Score” system that some feel are equally hard to understand and derive meaning.

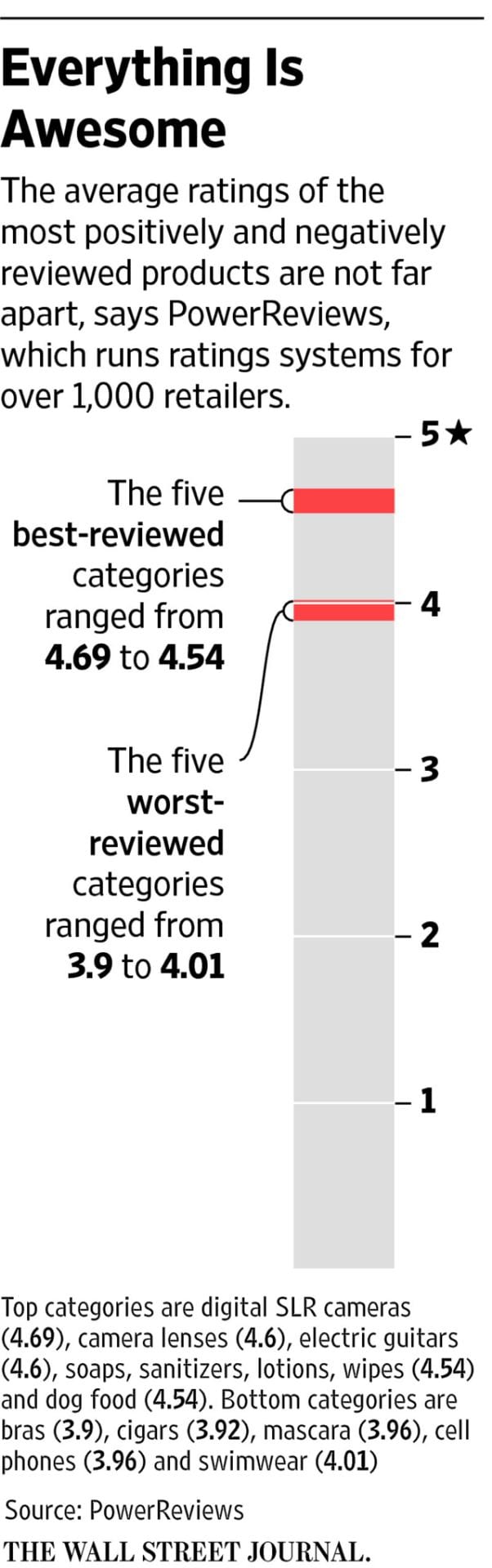

So what are Netflix and these other internet companies missing and how can we as educators learn from this lesson? They are certainly using a scale of levels that would align with best practices in SBG. But having a limited number of levels, be it two, four,  or six, is not enough. The Wall Street Journal article’s author, Geoffrey A. Fowler, cited a PowerReviews report that found that online product ratings average about 4.3 stars all together from over 1000 products that they measured. There really is not much of a range to speak of as this graphic shows. Is everything online really that good or is or there something else missing from the equation?

or six, is not enough. The Wall Street Journal article’s author, Geoffrey A. Fowler, cited a PowerReviews report that found that online product ratings average about 4.3 stars all together from over 1000 products that they measured. There really is not much of a range to speak of as this graphic shows. Is everything online really that good or is or there something else missing from the equation?

As educators, we need to be sure not to fall into this trap and provide levels which communicate nothing to the learner. Best practices in standards based grading can help provide a meaningful roadmap.

Let’s start with further consideration of the number of levels used. In On Your Mark (2015) Tom Guskey points out that educators commonly and erroneously believe that additional levels are needed to accurately classify performance. Dr. Guskey asserts that, “As the number of levels or categories increases, so do the number of classification errors.” As we increase the number of performance categories, we lower our chances of reliability. In other words, as we add more levels it decreases the likelihood that two teachers will arrive upon the same level of performance when measuring student achievement. Netflix started low and went lower with their number of levels so it appears there is no problem there. So is there a perfect number of levels to provide meaningful and accurate feedback?

Between two and six levels seems to be the most commonly noted ranges to measure performance according to professional literature. Ken O’Connor shares in How to Grade for Learning (2018) that “in a pure standards-based system, there would only be two levels – Proficient and Not (yet) Proficient.” This would give credence to the Netflix approach. However, O’Connor goes on to note that it is beneficial to distinguish in some way how close a student may be to proficient and also to acknowledge excellence beyond proficiency which provides rationale for going beyond the binary system.

This is where the importance of criteria and descriptors comes in. What do the stars mean? What do the thumbs represent? What are the levels of performance communicating? According to Netflix, the thumbs up and thumbs down model did lead to an increase of user ratings by 200%. The question then becomes what meaningful feedback did Netflix receive from that information versus their previous model?

There need to be clear values assigned to the levels that are used. In Standards-Based Learning in Action (2018), Schimmer, Hillman, and Stalets point out that in order for performance levels to be meaningful “They must tie language that describe a natural progression of quality from the simplest to the most sophisticated.” Schimmer, et. al., assert that “teachers must be able to describe (not just label) the differences between each level.” This language is what Netflix and other internet ratings are missing and what effective teachers and schools in an SBG environment are able to accomplish.

So Netflix and the rest of the internet, you have your guidance from the field of education and the SBG community. Educators, reflect as well and ensure that you are all following these best practices in regards to levels of performance. Learn from standards-based grading and slap some clear criteria and descriptors on your rating systems. You will get more meaningful feedback and we will have more success picking which show is really worth watching tonight.

Works Cited

Basperyras, Pascal, Netflix Recommendations are Broken…There’s an Alternative. Medium (June 26, 2018)

Fowler, Geoffrey A., When 4.3 Stars is Average: The Internet’s Grade-Inflation Problem, The Wall Street Journal (April 5, 2017)

Guskey, Thomas. On Your Mark (2015)

O’Connor, Ken. How to Grade for Learning (2018)

Schimmer, Tom, et al. Standards-Based Learning in Action (2018)

Image retrieved from https://www.digitaltrends.com/movies/netflix-ditches-star-ratings/

Leave a Reply