So, you are feeling good about the philosophy of standards-based grading and you understand the big picture. It is time to start implementing and you come to the realization that a philosophy only gets you so far. You need to transfer the student learning that is taking place in your classroom into meaningful and accurate measures of student achievement that you can report out on.

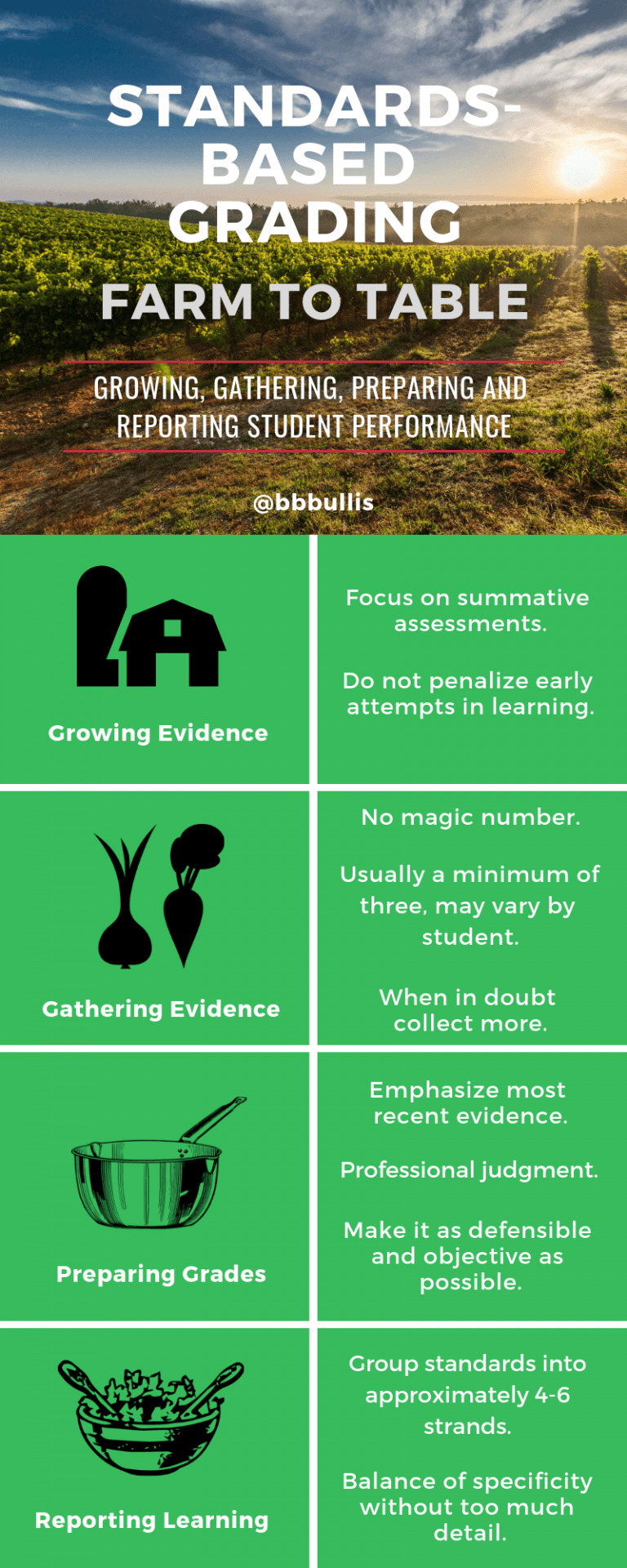

The questions start spinning in your head. What constitutes evidence of attainment? How much evidence do you need to gather? How do you calculate it? How does all of this translate into strands and get reported out? How do you take this process from farm to table? Help!

The good news is that there are many exceptional minds out there who have already thought this through and can provide the guidance that you need.

Let’s start at the farm with how to generate evidence of standard attainment. The clear consensus is that summative assessments (assessments of learning) should qualify as evidence and formative assessments (assessments for learning) should not. (Schimmer, et.al., 2018; Vatterott, 2015, Marzano, 2010) As Cathy Vatterott points out, “In a purely standards-based grading system, only summative assessment ‘counts’ in the final grade.” Think of formative assessment as planting the seeds and helping them grow versus summative assessment being the fully grown plants that are ready for harvest.

If you are wondering what may suffice as a summative assessment it may be easier to ask what would not suffice. As Ken O’Connor (2018) shares there are multiple methods and sources in which students can be summatively assessed, including oral, written, visual, or any combination of two or three of these methods (i.e. essays, posters, interviews, murals, demonstrations, brochures, simulations, performances, and much more). Essentially, anything that the teacher deems as communicating attainment of the standard could be considered; we should not feel bound to only traditional methods of assessment.

I do think it is important to note that all of the cautions related to not using formative assessment to determine grades are based on the premise that we do not want to penalize students for early attempts in learning. If we grade these early attempts they have the potential to skew overall grades farther down the road. However, looking at this topic through a different lens, if a student is showing clear evidence of mastering standards through their performance on formative assessments this could possibly be considered evidence of meeting the standard(s) assessed.

One example to illustrate this point is provided by Vatterott who describes a class using a checklist/rubric over time that formatively assessed several reading learning targets. She points out that this same information could eventually be used summatively as the student progresses and eventually meets the expectations. She shares that a “formative assessment may also be the first attempt at what will eventually be a summative assessment.”

Ok, but how much evidence do you need to gather? When it comes time to harvest the evidence it is important to understand that there is no magic number. This applies both to any standard you may be measuring or even how much evidence is needed from one student to the next for the same standard.

Schimmer, et. al. observe that teacher practices for data collection range from two to three indicators all the way up to fifteen or sixteen. As O’Connor points out, the experts usually suggest a minimum of three and “Ultimately, appropriate sampling for grading is about having enough of varied types of assessment information to make high-quality decisions when summarizing student achievement.”

When a student is consistent in their performance it makes it easy for us to measure that performance, but we know that is often not the case. Marzano advises that “the teacher has little option but to collect more information from the student when uneven patterns of scores occur.” O’Connor shares similar guidance with his rule of thumb, “if in doubt, you need another piece of evidence.”

O’Connor also promotes the idea of triangulating the evidence whenever possible. The idea here is to collect evidence from observing students, from student products, and from conversations with students. This will not always be possible if the standard is explicitly asking for a specific method, but the approach can generally be used to move us past relying on one type of evidence.

Ok, but how do you accurately calculate the student learning? It is time to take that harvest and prep the meal. There is no magical formula here that will save the day, but there are best practices to help guide you. In the end you are the expert regarding the growth of your specific students. No one else has the same level of understanding regarding the growth and achievement of your students and your professional judgment carries a lot of weight. That being said, you want to be as objective as possible and you want to make sure that the grading decisions you make are accurate and defensible.

One of the primary challenges in calculating grades is to abandon most traditional forms of grading that rely on percentages and arbitrary scales to determine student success. Schimmer, et. al. stress that teachers “should avoid at all costs” calculations that take into account how many questions a student incorrectly answered, as grading based on errors alone is not standards-based. Instead these authors promote the idea that “Professional judgment trumps numerical calculations when determining proficiency levels. Always go back to the question, has the student met the standard?” Guskey shares that “The most recent evidence should always be given priority or greater weight…the most accurate evidence is generally the evidence collected most recently.”

Finally, how do you clearly report out student learning? You are ready to put the meal on the table and you want to do it in a way that everyone can appreciate and hopefully enjoy. When it comes to report cards the idea of reporting out on strands that encapsulate multiple standards, instead of reporting one overall grade, is the best approach. Schimmer, et. al. share that “the information conveyed should be powerful and meaningful. Because of this, many schools choose to report on strands or domains instead of standards.”

Strands prevent students and parents from having to navigate a fifteen page report card of individual standards, but also provide more information than one overall grade provides. As Guskey (2015) points out “The information should be specific enough to communicate the knowledge and skills students were expected to gain but not so detailed that it overwhelms parents and others with data they do not understand or know how to use. Parents want to know how well their child is doing and whether or not that level of performance is in line with the teacher’s and school’s expectations.”

When it comes to the number of strands per subject area, Tom Guskey recommends four to six while Ken O’Connor suggests three to ten as being acceptable. The idea of reporting out on this range of strands complements most subject area curriculum standards quite nicely as most state and national standards have a similar number of themes that run throughout the various grade levels. These curricular standards may not always be a perfect fit, but they are a great place to start when identifying your own strands. As Guskey, et. al, (2011) pointed out “Using the broad strands…also meant that minor revisions in particular curriculum standards would not necessitate significant changes in the content or format of the report card.”

Worried that the the multiple strands creating more work? Guskey (2015) says not to fear as this procedure actually makes grading easier as teacher “no longer worry about how to weigh or combine that evidence in calculating an overall grade. As a result, they avoid irresolvable arguments about the appropriateness or fairness of various weighting strategies.”

There you have it, the farm to table approach for taking student performance from the classroom to the report card in a standards-based grading system. In the same way that every harvested plant will not be perfect you should not expect your grading system to be either. However, following these steps will increase objectivity and bring you closer to grading excellence.

Works Cited

Guskey, T. On Your Mark: Challenging the Conventions of Grading and Reporting. Solution Tree, 2015.

Guskey, T., Swan, G., and Jung, L. Grades That Mean Something, Phi Delta Kappan Magazine, October, 2011.

Marzano, R. Formative Assessment & Standards-Based Grading. Marzano Research, 2010.

O’Connor, K. How to Grade for Learning: Linking Grades to Standards, 4th ed. Corwin, 2018.

Schimmer, T., Hillman, G., and Stalets, M. Standards-Based Learning in Action: Moving From Theory to Practice. Solution Tree, 2018.

Vatterott, C. Rethinking Grading: Meaningful Assessment for Standards-Based Learning. ASCD, 2015.

January 31, 2019 at 10:58 pm

Excellently written post, Brian! Clear, concise and compelling answers to some very common SBG questions!